Amethyst Mapped Ignition

The Amethyst project is the result of a wish to apply today's engine management technology to classic cars. Many thousands of older cars are still in regular use, and bring great pleasure to their owners. Our aim was to improve their efficiency and emissions as far as we could at reasonable cost and without losing the essential character of the car.

Measured solely in terms of efficiency, most overhead valve engine designs of the 1950s and 1960s are not too far short of current standards. Their combustion chambers are reasonably compact and their compression ratios are reasonably high. Today's engines are very much lighter, quieter, cleaner, freer breathing, better balanced and better built from far superior materials. However, in most cases, the thermodynamic efficiency of classic engines is at least acceptably good. The principles of sound engine design were already well understood early in the 20th century. Most of the development work carried out over several decades has been concerned with approaching ever closer to a well-known theoretical ideal.

Most of the biggest improvements in engine performance over the last 40 years have resulted from advances in fuelling and ignition, rather than the engine block itself. It was quickly decided that any useful improvement to a classic engine's carburation would involve wholesale replacement at considerable cost. However, it appeared that useful improvements to the accuracy of the ignition timing could be made at moderate cost, with modifications that could easily be reversed if required.

Measured solely in terms of efficiency, most overhead valve engine designs of the 1950s and 1960s are not too far short of current standards. Their combustion chambers are reasonably compact and their compression ratios are reasonably high. Today's engines are very much lighter, quieter, cleaner, freer breathing, better balanced and better built from far superior materials. However, in most cases, the thermodynamic efficiency of classic engines is at least acceptably good. The principles of sound engine design were already well understood early in the 20th century. Most of the development work carried out over several decades has been concerned with approaching ever closer to a well-known theoretical ideal.

Most of the biggest improvements in engine performance over the last 40 years have resulted from advances in fuelling and ignition, rather than the engine block itself. It was quickly decided that any useful improvement to a classic engine's carburation would involve wholesale replacement at considerable cost. However, it appeared that useful improvements to the accuracy of the ignition timing could be made at moderate cost, with modifications that could easily be reversed if required.

The traditional advance mechanism

The standard centrifugal advance mechanism consists of a pair of sprung weights, which move outwards and turn the distributor cam as RPM increases. This mechanism was introduced in the 1920s and survived more or less unchanged until the introduction of electronic engine management in the late 1970s. Although it was a major step forwards when new, it has many limitations.

The first drawback is that the timing characteristic is completely determined by the two weights and springs. Typically, one spring is stronger than the other, and only comes into use at higher RPM. The advance characteristic can therefore only be the intersection of two nearly straight lines. A second drawback is that small variations cause big differences. Production variations in spring strength can cause very noticeable differences in the advance characteristic.

Friction and play in the mechanism can cause the ignition timing to change from one moment to the next. The standard advance mechanism has six bearings, four spring posts and one concentric shaft, all of which turn through small angles: an ignition advance of 10 degrees typically results when the weights turn through only 2 degrees. Servicing consists of letting two or three drops of oil fall through the contact breaker plate and hoping that they hit their target. Whether they actually do so presumably depends on the exact position in which the engine last came to rest. Distributors are often mounted in inaccessible places, so this maintenance step was regularly ignored anyway.

The first drawback is that the timing characteristic is completely determined by the two weights and springs. Typically, one spring is stronger than the other, and only comes into use at higher RPM. The advance characteristic can therefore only be the intersection of two nearly straight lines. A second drawback is that small variations cause big differences. Production variations in spring strength can cause very noticeable differences in the advance characteristic.

Friction and play in the mechanism can cause the ignition timing to change from one moment to the next. The standard advance mechanism has six bearings, four spring posts and one concentric shaft, all of which turn through small angles: an ignition advance of 10 degrees typically results when the weights turn through only 2 degrees. Servicing consists of letting two or three drops of oil fall through the contact breaker plate and hoping that they hit their target. Whether they actually do so presumably depends on the exact position in which the engine last came to rest. Distributors are often mounted in inaccessible places, so this maintenance step was regularly ignored anyway.

A new approach

|

|

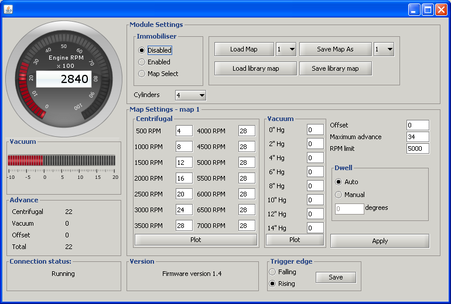

Amethyst is a small, discreet unit which can be mounted in the engine compartment. Wires go to the distributor, the coil and an optional immobiliser switch. The unit includes a vacuum sensor, which can be connected directly to the existing pipe from the inlet manifold. As with any modern engine, a microprocessor uses a look-up table to determine the correct ignition advance for any combination of RPM and load. Dwell is calculated automatically, and the unit includes a "soft" rev limiter.

The unit is configured via a USB connection, using a freely downloadable PC application. The first major improvement is that the advance characteristic can be set to exactly what the engine requires, without the constraints imposed by the two advance weights. Secondly, the unit's behaviour is fully repeatable, since the friction and play inherent in the traditional advance mechanism are absent. On the road, this means a sweeter, more responsive engine which will generally also prove more economical. Our 1967 MGB has covered over 30,000 miles since we bought it six years ago, mostly with an Amethyst unit fitted. Five years after the first Amethyst road tests, the unit is in full production and is available exclusively from Aldon Automotive Ltd. The traditionalAmethyst was recently reviewed by mgb-stuff.org.uk. You can read about their experiences here. |